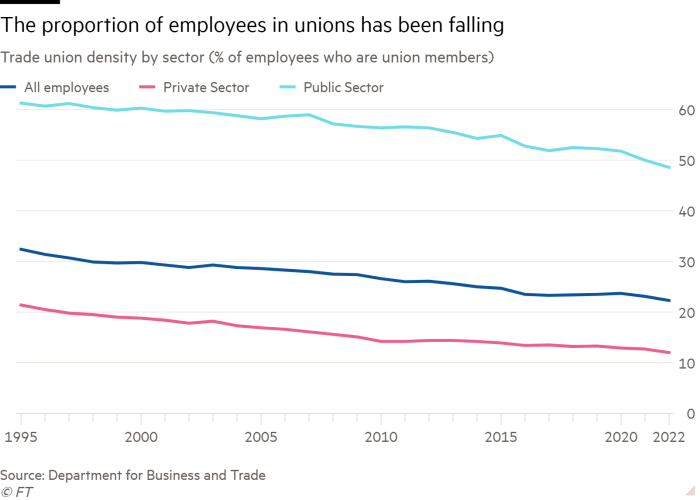

After more than a year of falling living standards, UK wages are finally outpacing inflation again, in no small part due to the efforts of trade unions.

Record growth of 8.5 per cent in average earnings reported this week was boosted by pay awards won on the back of the biggest wave of strike action in decades, with the Office for National Statistics citing the effect of deals in the NHS and the civil service. Unions have also won double-digit wage increases across a swathe of private sector companies.

“By any measure it’s been a massive year for unions,” Paul Nowak, general secretary of the Trades Union Congress, told the annual gathering of the UK’s organised labour movement in Liverpool this week.

But with ongoing strike disruption by doctors and rail workers testing public support, unemployment on the rise, and the collapse of retailer Wilko underlining the risks of further lay-offs, unions fear the window for action is closing.

“We’ve passed the peak,” said Mike Clancy, general secretary of the union Prospect, although he noted that there could be tough battles over public sector pay next year if inflation remained high.

Gary Smith, general secretary of the GMB, said that with layoffs looming at companies affected by the construction slowdown, workers could be afraid to push pay claims too far. “Things are starting to turn. There’s a sense that things are slowing down”.

Unions are also facing what some see as a near-existential threat in new legislation allowing ministers to mandate the provision of a minimum service during strikes in key sectors.

But while some union leaders are calling for a campaign of non-compliance with the new law, Clancy said there were “many ways to oppose it rather than shouting from the rooftops”, including alternatives to strike action, such as working to rule or bans on overtime.

The need for such tactics may only be temporary because with the Labour party far ahead in the polls and a general election expected next year, 13 years of Conservative-led government could soon be coming to an end.

Labour was was founded over a century ago as the political wing of the trade union movement and delegates at the TUC conference were cautiously buoyant about the possibility of its return to government. “We’ve had so many false dawns since 2010 that we aren’t taking this for granted,” said one union leader.

The agenda of party leader Sir Keir Starmer is too moderate for many union officials, especially those from more militant organisations, who accuse him of reheating the centrist policies of former Labour prime minister Tony Blair.

Starmer has binned most of his predecessor Jeremy Corbyn’s pledges of tax rises and nationalisations. But he has kept a wholesale package of measures designed to change the balance between employees and employers, dubbed the “New Deal for Working People”.

These include a promise to reverse anti-trade union legislation from 2016 and 2023, including the reviled “minimum service levels” law, and to make it easier for unions to enter workplaces, win recognition and set up collective bargaining arrangements in the private sector.

Christina McAnea, general secretary of Unison, said these reforms would be a priority, with unions currently struggling to recruit even enough members to replace those who have moved jobs or retired in the public sector, let alone to rebuild their much-diminished presence in the private sector.

Starmer has also promised to improve sick pay, ban fire-and-rehire practices and zero-hour contracts and introduce a right to disconnect where employees can log off from work emails.

But union leaders are nervous that this package could be trimmed back ahead of the election in an attempt to reassure business leaders. In July Labour softened some of its pledges — clarifying, for example, that its plan to introduce “basic individual rights from day one for all workers” would not preclude probationary periods for new staff.

“There are some very welcome policies . . . the difficulty is getting from promises and speeches through the hurly-burly of a very long election campaign . . . into a manifesto and then delivered through statute and then into the workplace,” said Mick Lynch, general secretary of the RMT rail union, which has carried out rolling strikes over the last year.

Sharon Graham, leader of the Unite union — which has scored some of the biggest wins in recent private sector pay disputes — accused Starmer of sitting on a “wobbly fence” over major issues.

Graham suggested that if Labour politicians did not “do what’s required”, unions could instead devote more of their resources to fighting disputes and become a “real workers’ movement”, rather than simply “waving money”.

“If you lose sight of what you’re in there to do, you’re not seeing what side you’re on and what we created you for,” she said.

Starmer has made a concerted push to increase Labour’s donations from wealthy individuals in order to reduce the party’s financial dependence on the union movement, with Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, last month ruling out a wealth tax should the party win the election.

McAnea said she was disappointed with the announcement. “They are going to have to look at a wealth tax,” she said. “I would hope that at some point in the future they will reconsider that.”

But despite the grumblings about Starmer’s increasing moderation over the last three years, he retains the broad backing of the union movement.

Clancy said that while unions would always want more, Labour had given a “cast-iron guarantee” to repeal anti-strike laws and a commitment to strengthen workers rights. “The reality is that we’re electing a government that is going to gradually address the fact that UK employers and their companies have had a decade and a half of untrammelled authority.”

Credit: Source link